Environmental Studies

As good stewards of the environment, MoDOT strives to be environmentally conscious with all of its transportation projects. Also, in order to comply with national and state environmental legislation, MODOT is mandated to consider the potential impacts of its projects on our state’s natural and social resources. Legislation such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 was passed in response to growing public concern for the environment. NEPA establishes a national policy to protect the environment, which includes the assessment of potential environmental impacts of all major federal actions.

MoDOT’s staff of natural and social science specialists are responsible for evaluating the impacts of all transportation projects on Missouri’s diverse array of natural resources. Those resources include: floodplains, wetlands, sensitive species, farmland, air and water quality, and wildlife habitats. MoDOT personnel also address concerns relating to noise and hazardous wastes. Furthermore, the Federal Highway Administration has established additional requirements for the protection and enhancement of resources such as publicly owned parks, recreation areas, and wildlife and waterfowl refuges. MoDOT must also consider all social and economic impacts of its projects on the human environment. After completing their environmental assessments, staff specialists will assist MoDOT's district personnel in avoiding, minimizing, or mitigating project impacts on the natural and human environment.

Environmental topics that MoDOT considers in the planning, construction and maintenance of Missouri's transportation system are presented in this article.

Air Quality

The Clean Air Act (CAA) requires each state to develop a state implementation plan (SIP) that establishes air quality objectives and regulations the state will follow. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) must approve each state’s SIP. Transportation conformity, as required by the CAA, ensures that federally funded or approved transportation plans, programs and projects conform to the air quality objectives established in the SIP. The EPA develops transportation conformity regulations with the Federal Highway Administration input and concurrence.

Federal standards have been established through extensive scientific review that set allowable concentrations and exposure limits for certain pollutants. Primary standards are to protect public health. Secondary standards are intended to prevent environmental and property damage (i.e., damage to crops, vegetation, buildings). Air quality standards have been established for six federally-identified pollutants:

- 1) ozone (or smog)

- 2) carbon monoxide

- 3) particulate matter

- 4) nitrogen dioxide

- 5) lead, and

- 6) sulfur dioxide

A geographic area with monitored levels that meet or do better than the primary standard for each of these pollutants is called an attainment area; areas that do not meet the primary standard for any one or more of these pollutants are called nonattainment areas. MoDOT is responsible for implementing the conformity regulation for transportation actions in attainment and nonattainment areas (e.g., the St. Louis area is a nonattainment area for ozone and particulate matter in Missouri).

Community Impact Assessment/Environmental Justice

Community Impact Assessment is a process that helps MoDOT understand how a proposed transportation activity may impact the local communities and the individuals within them. This process needs to begin at the earliest stages of the project and should be carried on throughout the decision-making. Environmental Justice is closely related and seeks to ensure that the proposed transportation activity will:

- Avoid, minimize or mitigate disproportionately high and adverse human health and environmental effects, including social and economic effects, on minority populations and low-income populations;

- Ensure the full and fair participation by all potentially affected communities in the transportation decision-making process; and

- Prevent the denial of, reduction in, or significant delay in the receipt of benefits by minority and low-income populations.

So, why is MoDOT concerned about how its projects may impact the local community? To begin with, MoDOT has acknowledged in its mission statement that our aim is “world-class transportation” and for it to promote “a prosperous Missouri” and that cannot happen if our projects leave the local community in worse shape after the project is built than it was in before. If a new road or just a wider road is needed, it's pretty much a guarantee that some new right of way will be needed and that new right of way will have to come from someone, but with careful study, the best design will have the least negative impacts on the community involved. Probably the biggest goal in community impact assessment is to help ensure that all segments of the community has the opportunity to let their interests and concerns be considered. And, yes, there are numerous laws, regulations and policies that must be followed. These include a variety that have been put into place to protect citizens from discrimination involving race, color, national origin, age, handicap/disability, religion or economic status.

The impacts from the large majority of MoDOT’s transportation projects are very minor as far as community impact assessment and environmental justice is concerned. While it can provide a major benefit to the traveling public, a resurfacing project or a minor widening project is unlikely to result in “disproportionately high and adverse impacts on any protected populations.” On the other hand, those same projects can enhance community life (for example: it can result in improved response time by emergency services).

However, the true benefit is for the local community to get the best value for each and every dollar spent on transportation and that value must be based on far more than just the construction of the road itself. In addition to affecting the emergency response time, the community impact assessment should consider things like:

- Will the project isolate portions of the community?

- Will this project encourage new businesses to move into the area or influence existing businesses to close or relocate?

- How will the project affect the tax base or property values?

- Will this project result in the loss of farmland or cause residents or businesses to be displaced?

- Does the project affect non-motorist access to businesses, public schools and other facilities?

- Has aesthetics been previously identified as a community concern?

Farmland Protection

Missouri has a long history of farming. Farming in the state annually produces crops and livestock valued at nearly $5 billion. Recognizing the importance of protecting farmland from conversion to non-agricultural uses by minimizing the impacts to it from federally funded programs, Congress passed the Farmland Protection Policy Act (FPPA) in 1981. Before farmland can be used by a federal project, it must be assessed to determine if prime, unique, statewide or locally important farmland would be converted to non-agricultural uses. This assessment is a collaborative process with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). If farmland is used in excess of parameters developed by NRCS, then the federal agency must take measures to minimize farmland impact. The benefit to the public is that MoDOT minimizes its impact to Missouri’s farmland to help preserve it for the present and future generations.

NRCS classifies farmland as prime, unique or of statewide or local importance based on soil type. Prime farmland has the best blend of physical and chemical characteristics for producing normal crops while requiring less human labor and less assistance from pesticides and fertilizer than farmland of statewide or local importance. Unique farmland is used for the production of specific high-value food items such as nuts and certain fruit or vegetables, and usually has the special combination of soil characteristics, moisture and location needed to produce high quality and high yields. Statewide or locally important farmland is designated by state or local agencies for the production of crops in a specific area, but is not of national significance.

Floodplain Management

What is the 100-year (One Percent) Floodplain and Regulatory Floodway?

Executive Order 11988 – Floodplain Management and subsequent federal floodplain management guidelines mandate an evaluation of floodplain impacts. When available, flood hazard boundary maps (National Flood Insurance Program) and flood insurance studies for the project area are used to determine the limits of the base (100-year) floodplain and the extent of encroachment.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Federal Highway Administration guidelines (23 CFR 650) have identified the base (100-year) flood as the flood having a one-percent probability of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. The base floodplain is the area of 100-year flood hazard within a county or community. The regulatory floodway is the channel of a stream plus any adjacent floodplain areas that must be kept free of encroachment so that the 100-year flood discharge can be conveyed without increasing the base flood elevation more than a specified amount. FEMA has mandated that projects can cause no rise in the regulatory floodway, and a one-foot cumulative rise for all projects in the base (100-year) floodplain. For projects that involve the state of Missouri, the State Emergency Management Agency issues floodplain development permits. In the case of projects proposed within regulatory floodways, a "no-rise" certificate, if applicable, should be obtained prior to issuance of a permit.

How are Floodplains Beneficial?

Floodplains provide a number of important functions in the natural environment, including creating wildlife habitat, providing temporary storage of flood water, preventing heavy erosion caused by fast moving water, recharging and protecting groundwater, providing a vegetative buffer to filter contaminants, and accommodating the natural movement of streams. MoDOT avoids or minimizes encroachment into floodplains whenever possible in order to preserve these values for the future. MoDOT conducts engineering analyses of floodplain impacts to avoid and reduce impacts by bridging wherever possible. The use of bridges serves a dual function by reducing wetland disturbance while minimizing construction impact in the floodplain. Where feasible, the proposed crossings are located adjacent to existing road crossings where the additional impact would be minimized.

FEMA Buyout Sites

The Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973, as amended by the Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1988 (The Stafford Act), identified the use of disaster relief funds under Section 404 for the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), including the acquisition and relocation of flood damaged property. The Volkmer Bill further expanded the use of HMGP funds under Section 404 to “buyout” flood damaged property, which had been affected by the Great Flood of 1993.

There are numerous restrictions on these FEMA buyout properties. No structures or improvements may be erected on these properties unless they are open on all sides. The site shall be used only for open space purposes, and shall stay in public ownership. These conditions and restrictions (among others), along with the right to enforce same, are deemed to be covenants running with the land in perpetuity and are binding on subsequent successors, grantees, or assigns.

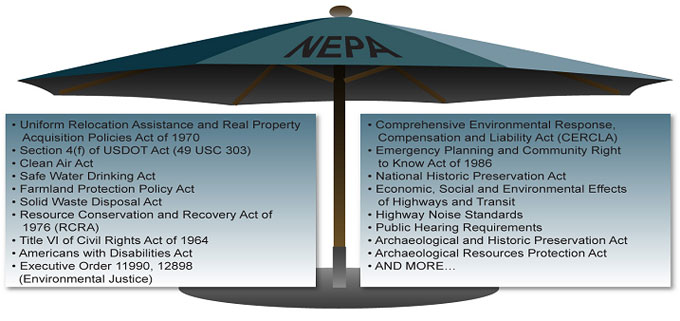

NEPA

The Federal Highway Administration’s compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) calls for all environmental protection requirements and enhancement goals to be completed as part of a coordinated review process that includes and considers the input of other agencies and the public through established coordination and a public involvement process. Evidence of this compliance must be contained in appropriate documentation.

The purpose of documenting the NEPA process is twofold: to provide complete disclosure of the environmental analysis process and to present the results of the analysis (i.e., the decision). Different kinds of transportation projects will have varying degrees of complexity or potential to affect the environment. The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) regulations implementing NEPA identifies three classifications of actions, defining the way that compliance with NEPA is documented in terms of the action's impacts:

- Categorical Exclusions are for actions that do not individually or cumulatively have a significant environmental effect.

- An Environmental Assessment is prepared for actions in which the significance of the environmental impact is not clearly established.

- An Environmental Impact Statement is prepared for projects where it is known that the action will have a significant effect on the environment.

Although the size and apparent complexity of the three levels of NEPA documentation is quite different, they all serve the same purpose, to achieve NEPA's goals of a collaborative decision making process and ultimately to make the public aware of the rationale behind transportation decisions.

The Council on Environmental Quality – Executive Office of the President determine the need for a guide that provides an explanation of NEPA, how it is implemented and how people outside the Federal government can better participate in the assessment of environmental impacts conducted by Federal agencies. The result is A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA: Having Your Voice Heard.

Noise Assessment

Sound (noise) occurs when an ear senses pressure variations or vibrations in the air. Noise is unwanted sound. A person’s brain associates a subjective element to a sound and an individual reaction is formed. Studies indicate that the most pervasive sources of noise in our environment today are those associated with transportation. Highway traffic noise tends to be a dominant noise source in both the urban and rural environment.

Public concern about noise led to federal legislation in 1970 that authorized the use of federal-aid highway funds for measures to abate and control highway traffic noise. The guidelines in the MoDOT Noise Policy are used to determine the need, feasibility, and reasonableness of noise abatement measures and provide the basis for statewide uniformity in traffic noise analysis.

The Federal Highway Administation regulations require MoDOT to:

- 1) identify traffic noise impacts and examine potential mitigation measures;

- 2) incorporate reasonable and feasible noise mitigation measures into its highway projects; and

- 3) coordinate with local officials to provide helpful information on compatible land use planning and control during the planning and design of a highway project.

The regulation makes a distinction between projects for which noise abatement is considered as a feature in a new or expanded highway and those for which noise abatement is considered as a retrofit feature on an existing highway.

Public Lands

MoDOT monitors all federally funded roadway improvement projects for compliance with Federal regulations concerning the use of public lands, specifically Section 4(f) and Section 6(f) requirements. The benefit to the public is that MoDOT considers the impact on using public land in the planning process and then attempts to minimize and mitigate when impacts are unavoidable.

What is Section 4(f)?

Section 4(f) refers to the original section within the Department of Transportation (DOT) Act of 1966, which set the requirement for consideration of park and recreational lands, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and historic sites in transportation project development. 4(f) resources include any publicly owned park, recreation area, or wildlife refuge or any publicly or privately owned historic site.

Before approving a project that “uses” a Section 4(f) resources, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) must find that there is no prudent and feasible avoidance alternative AND that the selected alternative minimizes harm to the resource. If there is a prudent and feasible alternative that completely avoids 4(f) resources, it must be selected. A feasible and prudent alternative avoids using Section 4(f) property and does not cause other severe problems of a magnitude that outweighs the importance of protecting the Section 4(f) property.

With MoDOT’s recommendation, FHWA decides whether Section 4(f) applies to a resource, reviews assessments of each alternative’s impacts to 4(f) properties, and determines whether the law allows for the selection of a particular alternative after consulting with the Department of the Interior.

What is Section 6(f)?

Section 6(f) is part of the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act, which was designed to provide restrictions for public recreation facilities funded with LWCF money. The LWCF Act provides funds for the acquisition and development of public outdoor recreation facilities that could include community, county, and state parks, trails, fairgrounds, conservation areas, boat ramps, shooting ranges, etc. Facilities that are LWCF-assisted must be maintained for outdoor recreation in perpetuity and therefore require mitigation that includes replacement land of at least equal value and recreation utility.

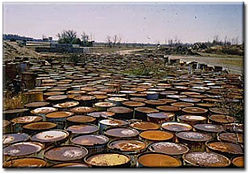

Solid and Hazardous Waste

Properties containing hazardous and nonhazardous solid wastes are frequently encountered by MoDOT in new right of way acquisitions. Examples of the types of land uses typically associated with hazardous waste sites are available. MoDOT’s goals for addressing hazardous and solid wastes are to: 1) avoid unacceptable cleanup costs and legal liability and 2) comply with federal and state laws and regulations regarding cleanup.

The MoDOT Environmental Specialist evaluates project corridors for waste sites, provide management and oversight of waste sites acquired, and monitor projects for compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Any unknown sites and/or wastes found during project construction will be handled in accordance with federal and state laws and regulations. MoDOT has the capability to collect samples and analyze for a variety of constituents, including but not limited to volatile organics and heavy metals. The Missouri Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) is contacted for coordination and approval of required activities as needed.

Laws and Regulations

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) of 1976 gives the federal government Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to regulate the disposal of hazardous waste. The EPA has delegated authority for executing most of the requirements of RCRA in Missouri to the MDNR’s Hazardous Waste Program. The Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendment (HSWA) of 1984 mandates corrective action at hazardous waste facilities for all releases of hazardous waste to the environment and includes provisions to regulate underground storage tanks.

The MDNR website contains more detailed information on the RCRA and these other these laws.

- The Missouri Hazardous Waste Management Law and the Petroleum Storage Tank Law address the issues of generation, management, and disposal of hazardous waste; cleanup of hazardous waste and hazardous substance releases; management and removal of petroleum storage tanks; and cleanup of leaking petroleum storage tanks.

- The Toxic Substance Control Act (TSCA) of 1976 was enacted to test, regulate, and screen all chemicals produced or imported into the United States. TSCA amendments enacted in July 1979 prohibit the production and distribution of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and regulate the labeling and disposal of PCBs.

- Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980, commonly know as Superfund, covers abandoned or uncontrolled wastes.

- The State Registry of Abandoned and Uncontrolled Sites of 1983 authorized the establishment of emergency response activities in the state to respond to hazardous substance releases.

- Brownfields and Voluntary Cleanup. The MDNR Hazardous Waste Program's Voluntary Cleanup Section administers Missouri's Voluntary Cleanup Program, established by the state legislature in 1994 to provide state oversight for voluntary cleanups of properties contaminated with hazardous substances.

- Petroleum Underground Storage Tanks (UST). In 1984, RCRA established a regulatory program for underground storage tanks, RCRA Subtitle I. The Missouri law governing the use of UST systems is found in Chapter 319.100-139 RSMo.

- Solid Waste Management Law. The Solid Waste Management Law provides the framework for the management of municipal solid waste, industrial and special waste.

Threatened and Endangered Species and Unique Communities

MoDOT considers the impact its projects will have on threatened and endangered species, which includes potential impacts to rare plants, animals, critical habitat and unique natural communities (e.g., caves). Approximately 745 plant species and 515 animal species in the United States are federally listed as threatened or endangered (T&E). However, only 10 federally listed plants and 19 federally listed animals (in addition, there are 7 candidates for federal listing) are known to occur in Missouri.

Federal laws require the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and MoDOT to thoroughly address any potential impacts their projects might have on federally listed T&E species and eliminate or minimize those impacts. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA) provides for the protection of threatened and endangered species, both plants and animals, and the habitats that are considered critical to the survival of these species, e.g., breeding, nesting, roosting and foraging areas. The ESA additionally requires FHWA and MoDOT to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) regarding their projects and measures that can be implemented to minimize or eliminate project impacts to these species. The USFWS is empowered as the chief administrative, regulatory and enforcement agency regarding threatened and endangered species and their critical habitats.

MoDOT projects must also address potential impacts to state listed species. The State of Missouri also maintains endangered species legislation that protects these species. The state Endangered Species Act and the Missouri Wildlife Code protect state listed species. The Missouri Cave Resources Act protects caves from trespass, vandalism, contamination and destruction. The Missouri Department of Conservation is the administrative, regulatory and enforcement agency for state sensitive species.

The state of also tracks the status of approximately 1,036 plant and animal species that are considered rare in the state. Of these, 67 are listed as state endangered.

What is an endangered species?

An endangered species is a species that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

What is a threatened species?

A threatened species is a species that is likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future.

What is an endemic species?

An endemic species only occurs in a particular area. Species that are endemic to Missouri only occur in Missouri.

| This project involves the removal of Eastern Hellbenders during the construction activities to replace an existing bridge in the Ozark region in southern Missouri. Hellbenders will be housed at Mo Department of Conservation’s Shepherd of the Hills Hatchery during bridge construction. Upon completion of the bridge, and removal of the old bridge, habitat (large rocks) will be augmented into the river, and hellbenders will be release back into the river. |  |

| MoDOT employees discovered a bald eagle nest with two adult birds and two nestlings along the proposed new alignment for U.S. Route 54 in Camden and Miller counties. MoDOT environmental specialists worked closely with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Mo Department of Conservation. Together they determined that the best course of action would be to wait for the eagles to leave the nest, and then remove it before the eagles returned the following winter to start the nesting process again. By removing the existing nest, the eagles can return to the lake area, but would build a new nest away from all the new development. |  |

Water Quality

Water quality can be defined as the current status or condition of the water in a specific aquatic ecosystem. It is much easier to describe what poor water quality is than to describe what conditions are considered good water quality. Many of the lines between good and poor are stream specific. Each watershed has some natural buffering capacity. This allows the water to adapt and compensate for normal changes in the environment such as leaching from the soil or the occasional heavy rain.

MoDOT is responsibility to implement control measures to prevent the excessive release of sediment and pollutants into nearby waterways whenever one acre or more of land is disturbed for roadwork. Links to Water Quality legislation, policies, and guidance is located on the Federal Highway Administration’s website.

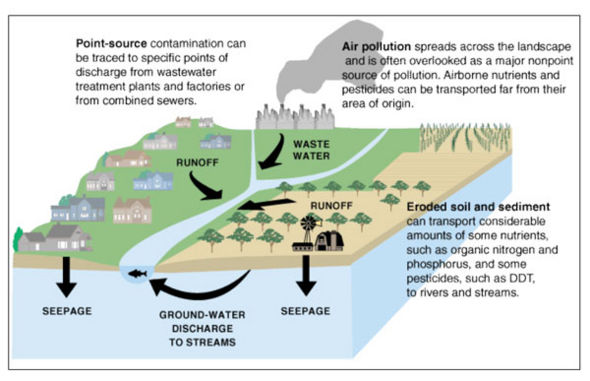

Water Pollution

Pollution occurs when conditions exceed the watershed’s ability to compensate for the changes. Polluted water may be discolored, possess a coating on the bottom of a stream, or may show no visible sign at all of pollution. There are many different kinds of pollution. The two major categories are point source and non-point source.

Point Source Pollution

Point source pollution comes from a defined, specific source such as a discharge pipe from a factory, a municipal sewage treatment plant, or a power generating station. The state’s Clean Water Laws as well as the federal Clean Water Act have made great strides towards identifying, controlling and cleaning up point source pollution.

Non-Point Source Pollution

Now that much of the point source pollution is being controlled, problems are arising that were previously overshadowed. Non-point source pollution (NPS) is being recognized as a major factor in the deterioration of today’s watersheds. Section 319 of the Federal Clean Water Act covers NPS pollution.

The most common types of non-point source pollution agriculture, erosion and sedimentation, and acid rain. Agriculture is a very serious source of NPS because there are so many kinds of pollution generated. The two most likely pollutants from agriculture are nutrients and sediments. Many of the pesticides and fertilizers used today have a tendency to be washed off of plants and filter into waterways through runoff, increasing nutrient loads. Nutrient and sediment levels increase when unprotected streams run through livestock pastures.

Erosion and sedimentation are also very common pollutants. Often excess amounts of solids enter waterways because of runoff. Construction sites, fallow fields and other areas of unprotected soil are extremely prone to large amounts of erosion. Poor forest management practices, such as clear cutting a hillside can also result in increased erosion. One method of decreasing erosion and sedimentation is with the protection and establishment of riparian buffers.

Acid rain or acid precipitation is becoming a common pollution source. Car exhaust as well as other discharges spouts compounds into the air. As clouds form and water vapor mixes with the gases, acids are formed. Sulfuric and nitric acids are the two most commonly found. When the clouds release the water as precipitation, these acids are carried down to earth and drain into waterways.

SWMP and MS4

Stormwater runoff is also a problem. Though it may not contain many pollutants, the unrestricted dumping of a large volume of water is detrimental in itself. The streams are accustomed to gradual flow into a waterway, not the forceful rush often associated with storm drains. The extra flow raises levels above normal often causing flooding and erosion. The increased flow of water also impacts aquatic habitat, changing the character of the stream from a quiet pool to a rushing, tumbling surge. Many organisms will not inhabit such fast-moving water. Refer to MoDOT’s Stormwater Management Plan and the Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems permit program information.

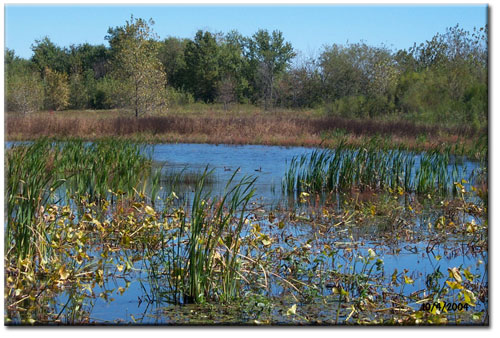

Wetland and Stream Protection

The Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972 requires the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and MoDOT to evaluate every project and determine whether the project could have a negative impact on any waters of the U.S. including wetlands, streams and special aquatic sites. FHWA and MoDOT must use the best available scientific information and the 1987 Corp of Engineers’ Wetland Delineation Manual to evaluate their projects and they must provide data to support their determination of impact.

Under the Sections 401 and 404 of the CWA, no action can be taken that will fill waters of the U.S. without first obtaining authorization under a nationwide or individual permit, depending on the amount of impacts.

- Section 404 of the CWA requires that all federal, state and public entities obtain a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE) before placing dredged or fill materials into waters of the U.S. as defined in 33 CFR Part 328 “Definition of Waters of the United States.”

- Section 401 of the CWA requires consultation and Water Quality Certification (WQC) with the state — Missouri Department of Natural Resources (MDNR). State legislation has removed MDNR's authority to condition nationwide permits (NWP's) for MoDOT highway and bridge projects. However, all activities that require individual permits and most requiring general permits will subsequently require WQCs.

MoDOT project concerns relating to waters of the U.S. (streams, wetlands and special aquatic sites) include potential stream impacts at linear crossings, filling of jurisdictional wetlands, stream channelization, and filling of designated special aquatic sites. Other 404 related concerns that pertain to the design and/or construction of MoDOT projects include avoiding work in streams during the spawning periods, providing notification to the Corps when working in sensitive watersheds, and addressing fish and aquatic life passage issues when building multi-cell box culverts in select streams. The handout “Streams, Wetlands and MoDOT” illustrates the resources, impacts, and mitigation that are involved in the 404 permit process.

If you are interested in owning a wetland site, please call 1-888 ASK MODOT.

| Typically, if the COE issues a Nationwide Section 404 permit for a MoDOT project and the permanent impact (i.e., loss) to jurisdictional wetlands is greater than 0.1 acre, then wetland mitigation is required. Mitigation for impacts greater than 0.1 acre often require additional right of way. A wetland design needs to be incorporated into the project or arrangements made for a stand-alone project. Where available, the district may have the option of using available credits in a mitigation bank for wetland mitigation. | |

Stream mitigation is required when permanent impacts exceed 0.1 acre of fill in stream channels below the ordinary high water mark or if other stream impacts (i.e., channelization) exceed Nationwide Permit limits. Mitigation can involve on-site design and/or utilization of the Stream Stewardship Trust Fund. Stream mitigation may also be incorporated with threatened and endangered species habitat improvement such as the Indiana bat. An example of stream mitigation is the Low-Water Crossing Retrofits.

|

|